夢(1)

夢のシンボルを理解する努力を惜しまないのであれば、夢はもっとも興味深い情報を提供してくれる。ただし、夢は売買のような世俗的な事柄とはほとんど関係ないことも事実だ。だが人生の意味が、仕事や銀行口座が満たすような人間的な深い欲求だけで説明されつくせるわけがない。

ブライアン・クラーク著 咲耶まゆみ訳

By Brian Clark Translated by Mayumi Sakuya

English text to follow.

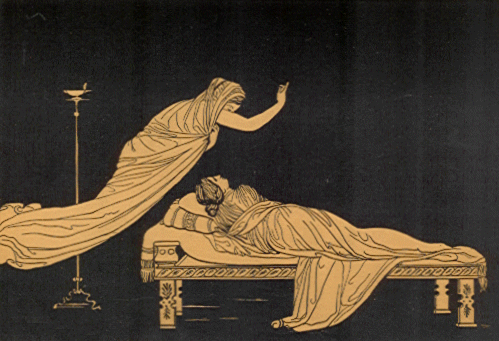

夢劇場

夢の国では、私たちは目が覚めている時に経験する日常の会社や経済的なプレッシャーからは遠く離れる。眠りの中では、私たちは別世界にいる。魂に近い世界だ。夢見は心を浄化する。夢に取り組むことは魂作りの取り組みだ。

夢を見るとき、私たちは外にある現世のイメージを吸収し、感じ、処理する。夢劇場では、個人的な経験、反応、欲求、情緒などが夢を作る。夢は主観的に想像性をもってストーリーを内観することを私たちに求め、精神とのさらに深いつながりを促す。夢は私たちの内側の人生と目が覚めている時の現実の間の連続性をもたらす。

夢と向き合うことで、夢の内容をさらに意識に自覚させることができる。例えば、母親、父親、兄妹、友人、敵、恋人、裏切り者などの夢を見たとしよう。彼らが呼び起こすイメージや気持ちは魂の部屋の中で感じられる。彼らのイメージを内側で内観する。それらが自分にとってどんな意味があるかを考えると、イメージはより象徴的になり、額面通りの意味を失ってくる。そして、内側にあるイメージに対する気持ちが生じさせ、その代わりに、これらの気持ちは、自分の中にあるその領域についてどう感じているかを考えさせる。実在する人物となって夢に現れるものの、これらのイメージを内在化し、外の世界が内側の世界を反映していることを意識することが魂作りにつながる。

同じように、ホロスコープと向き合うことも魂作りのための取り組みだ。ホロスコープのシンボルも私たちの人生に登場する人々や場所を表す。夢に出てくる母親、父親、兄妹、友人、敵、恋人、裏切り者もホロスコープに如実に象徴されることもある。ホロスコープは実在の人物を表すだけでなく、ホロスコープのシンボルを通して魂が語るその人に対する内面のイメージをも表す。個人の歴史、経歴、事実も重要である場合もあるが、これらは魂の歴史の要素ではない。夢やホロスコープのイメージに対する人の判断は魂と相反する。

内側のイメージは、その人物が自分にとってどんな意味を持つのか、自分のどの部分を彼らが象徴しているのか、そしてなぜ自分の夢に出てくるのかなどを考えさせる。アストロロジャーは、これらを外側でなく、内側の人物としてのイメージを内観したり、考えたりすることを促すことが出来る。従ってホロスコープを夢として考え、チャートを活発な想像として見ることもできる。夢と同様、これらイメージの全てがホロスコープの中にある。だから、イメージは外側の世界だけに属するのではなく、個人の心象風景にも存在するのだ。これらのイメージを魂の観点から考え始めると、個人は夢やホロスコープが表す額面通りの人だけではなくなり、内側の魂の人生の一部になってくる。夢やアストロロジーは、喚起されるイメージを通して、外の環境と内側の世界をつなげる手助けをするのだ。

夢も占星学も両方とも予言や神託のような性質を持つ。それらの言語は象徴的で隠喩的であり、意味を理解するための伝統や教義を持つ。しかし、予言は文字通りのものではなく、謎かけを通してその意味が与えられる。そのために、夢やホロスコープのシンボルやイメージが持つ多次元的な意味や微細な特質を尊重しながらアプローチする必要がある。アストロロジャーやドリームワーカーたちは、神託のようには個人の歴史、関係する事柄や感情を完全に知ることが出来ない場合がある。そのため、私たちはイメージや象徴に対する論理的な知識を保留にして、象徴に関する知識からではなく、個人の体験を背景に傾聴するべきだ。こうすることで、額面通りの解釈から魂の受容へと移行できる。

夢の歴史

「起きなさい、アリス!」アリスの姉は言った。「なんとまあ、長い間眠っていたこと!」

…そこでアリスは起き上がって走り出した。走りながらアリスは思った。「なんて素敵な夢だったのかしら」

ルイス・キャロルが想像した幻影の国でアリスは何と素晴らしい夢の時間を過ごしたことだろう。キャロルの先人たちの叙事詩人、脚本家、神話作者、作家たちと同じようにキャロルも不合理で奇妙な事柄、つまりアリスが地下で見つけたような人生の側面をクリエイティブに表現する手段として夢を使った。

20世紀の夜明け、シグムンド・フロイトは書籍『夢判断』を出版し、長年忘れ去られていた古代の夢解釈を精神分析の最前面にもたらした。出版直後、フロイトは彼の本に影響力があまりないことを嘆いた。しかし実際は、フロイトは精神分析学のみならず、人気の高い文化や文学において夢を回帰させた立役者であった。夢と共にアストロロジーも再び目を覚ました。

欧米文学の中では、キャロルやフロイトのほぼ3千年前、夢はすでに叙事詩を通して謳われ、再度伝えられ、記述されてきた。ホメロス(BC850年頃のギリシャの盲目叙事詩)は、叙事詩『オデュッセイア』の中で、夢を詩の登場人物の宿命パターンを作る神聖な力と結びつけた。これらは、西洋文化の感動的な文学に夢が常に織り込まれることになる予兆だった。フロイトの約2千年前、アルテミドルス(西暦2年の哲学者)もまた『夢判断(Oneirocritia )』を書いている。夢に関する5冊の本からなる古代ギリシャの教科書『Oneirocritia 』は、初めて世に知られた夢に関する作品である。

紀元前5世紀になると、古代ギリシャ人は睡眠や夢の回復力を使った癒しの儀式を様式化した。癒しの神アスクレピオスの聖域で、巡礼者や患者たちがアバトン(聖なる仮眠所:患者の夢にアスクレピオスが現れ、お告げに従って祭司が治療を施した場所)に入り、癒しの夢の準備のために横になって眠った。癒しの歴史では、夢は魂の活力の元であり、形ある日常世界と目に見えない魂の世界がつながるようにした。

現代的な見方からすると、夢は内なる世界に近づき、慣れ親しむための方法になったと言える。今日の情報や解釈に基づいた考え方とは異なり、古代では癒しの夢は神の訪問であり、夢の中そのものが癒しであると認識された。

ドリームワークは、魂に触れることを手助けする長い歴史を持つ神聖な伝統だ。フロイト、カール・ユング、ジェームズ・ヒルマン等心理療法士たちのお蔭で認知された。夢に取り組むことは、古代の神と対話の方法を再現するという事だ。そしてこのプロセスは、アストロロジーのそれに似ている。

Dream (1)

Dreams provide the most interesting information for those who take the trouble to understand their symbols. The results, it is true, have little to do with such worldly concerns as buying and selling. But the meaning of life is not exhaustingly explained by one’s business life, nor is the deep desire of the human heart answered by a bank account’

by Brian Clark

In the Theatre of Dreams

In the country of dreams we are far away from the daily corporate and economic pressures of life that we experience when awake. In sleep we inhabit another world, one more akin to the soul. Dreaming is a cathartic aspect of psychic life. Working with our dreams is an act of soul-making.

When we dream, our life’s outer and worldly images are absorbed and felt and processed. In the theatre of our dreams our personal experiences, reactions, desires and emotions author the account for the dream. The dream asks us to reflect upon its narrative from a subjective and imaginative perspective stimulating a deeper relationship with our psychic life. Dreams provide continuity between our inner life and waking reality.

Through reflecting on the dream its contents become more consciously internalised. For instance when we dream of our mothers or fathers, brothers or sisters, friends or enemies, lovers or betrayers, the images and feelings they evoke are felt inside the chamber of the soul. We consider their image inside of us. As we contemplate what they mean to us, their image becomes more symbolic and less literal, allowing feelings to develop for the image they hold inside of us. In turn, these feelings direct us to consider how we feel about this part of ourselves. Even though they personify an actual person, soul making is the act of internalising these images so that the world outside of us becomes a more conscious reflection of our inner world.

In a similar way working with the astrological horoscope is an act of soul making. Its symbols also represent the people and places of our lives. Even though the mother, father, brother, sister, friend, enemy, lover or betrayer of the dream can be accurately illustrated in the horoscope, it is not just the actual person that the horoscope delineates, but also the inner image of that person which the soul speaks of through the symbols of the horoscope. Personal history, biography and factual details are significant to the case presented but these are not the elements of a soul history. Human judgments about either dream or horoscopic images are contrary to the soul.

With inner images we are confronted with what the person means to us, what parts of ourselves might they characterise and why they are in my dream. Soul making can be encouraged by the astrologer when they facilitate the process of internalising images through reflection and consideration of the horoscopic images as inner, not outer, figures. Therefore we might contemplate the horoscope like a dream and working with the chart like active imagination. Like the dream, all these images are in the horoscope; therefore they belong not only to the outer world, but to the internal landscape of the individual. As we begin to consider these images more soulfully the individual is no longer exclusively the literal person of the dream or the horoscope, but part of our inner soul life.*1 Dreams and astrology help make connections between the projective outer environment and the inner world through their evocative imagery.

Both are divinatory and oracular by nature. The language of dreams and astrology is symbolic and metaphoric and each process has traditions and tenets which attempt to make their meanings accessible. But divinatory art is never as literal as we would like and its significance is usually dispensed through riddles; therefore we need to approach the symbols and images of the dream and horoscope with respect for their multi-dimensional meanings and subtle essences. Like oracles, astrologers and dream workers may not fully know the individual’s history, associations or feelings; therefore we need to suspend our logical knowing of the images and symbols to listen to them in the context of the individual’s experience, not from a learnt perspective of the symbol. In this way we move from more literal interpretations to more soulful perceptions.

The Tradition of the Dream

‘Wake up, Alice dear!’ said her sister. ‘Why, what a long sleep you’ve had!’

……..So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.*2

And what a wonderful dreamtime Alice had in the phantasmagorical land of Lewis Caroll’s imagination. Like epic poets, playwrights, mythmakers and storytellers before him Lewis Carroll used the dream as a means to creatively express the irrational and the bizarre, the aspects of life Alice found underground.

At the dawn of the 20th Century Sigmund Freud published his book The Interpretation of Dreams and brought the long-forgotten yet ancient tradition of dream interpretation to the foreground of psychoanalysis. Shortly after publishing he bemoaned that his book had little impact; however in reality, Freud was a seminal vessel for the return of the dream, not only to psychoanalysis but popular culture and literature as well. Alongside the dream, astrology reawakened.

In Western literature dreams had already been sung, retold and written down through epic poetry, tragedy and literature for nearly three millennia before Caroll and Freud. Homer in The Odyssey used dreams to link the dreamer with the divine forces pattern-making the fate of his characters. These were a foretaste of the dreams that would be consistently woven through inspirational literature of Western culture. Artemidorus, nearly two millennia before Freud, had also written The Interpretation of Dreams. Oneirocritia, an ancient Greek text comprising five books on dream interpretation is the first known Greek work on the subject.

By the 5th Century BCE the classical Greeks had formalised healing rituals drawing on the restorative powers of sleep and dreams. In the sacred precinct of the healing god Asclepius pilgrims and patients would enter into the Abaton to lie down and sleep in preparation for the healing dream. These early ideas thought the god visited individuals during the sleeping trance through their dream visions. In healing traditions the dream was the life blood of the soul and ensured the contact between the mundane world of body and form and the invisible world of soul.

From a modern viewpoint the dream becomes the way to access and befriend the inner world. Contrary to the informational and interpretative paradigms of modern day, healing dreams were acknowledged as a visitation of the god and that in itself was the healing.

Dreamwork is a long established sacred tradition that facilitates contact with the soul. Thanks to Freud, Carl Jung, James Hillman and other psychotherapists it has been re-cognised. Working with our dreams restores contact to the ancient ways that promoted communication with the gods, a process akin to astrological work.

Continue to “Dream 2”.

*1. James Hillman in The Dream and the Underworld, 96 describes it in this way: ‘The more I dream of my mother and father, brother and sister, son and daughter, the less these actual persons are as I perceive them in my naïve and literal naturalism and the more they become psychic inhabitants of the underworld. As they rise into the vision of my nights and I mull and digest their comings and goings, the family becomes familaris, internal accomplishments, no longer quite the literal people I engage with daily.’

*2. Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Bramhall House, New York: NY, 162

関連記事

- 土星-天王星のサイクル: 2021年のウエイニング・スクエアに関する考察 (Part 2)

- 土星-天王星のサイクル: 2021年のウエイニング・スクエアに関する考察 (Part 1)

- パンとパンデミック:山羊座時代の愛(1) Pan and the Pandemic(1)

- パンとパンデミック:山羊座時代の愛(2) Pan and the Pandemic(2)

- 親密な関係 – 8ハウス Intimacy – The Eighth House(Part 1)

- 親密な関係 – 8ハウス Intimacy – The Eighth House(Part 2)

- ヘスティアとともにある家(ホーム) At Home with Hestia

- 夢 Dream(1)

- 夢 Dream(2)

- 夢 Dream(3)